Hacktiv8-PTP Python For Data Science // S.1 // Introduction, Data Types, and Variables

Python is a high-level, interpreted scripting language developed in the late 1980s by Guido van Rossum at the National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science in the Netherlands. The initial version was published at the alt.sources newsgroup in 1991, and version 1.0 was released in 1994.

Python 2.0 was released in 2000, and the 2.x versions were the prevalent releases until December 2008. At that time, the development team made the decision to release version 3.0, which contained a few relatively small but significant changes that were not backward compatible with the 2.x versions. Python 2 and 3 are very similar, and some features of Python 3 have been backported to Python 2. But in general, they remain not quite compatible.

Both Python 2 and 3 have continued to be maintained and developed, with periodic release updates for both. As of this writing, the most recent versions available are 2.7.15 and 3.6.5. However, an official End Of Life date of January 1, 2020 has been established for Python 2, after which time it will no longer be maintained. If you are a newcomer to Python, it is recommended that you focus on Python 3, as this tutorial will do.

Python is still maintained by a core development team at the Institute, and Guido is still in charge, having been given the title of BDFL (Benevolent Dictator For Life) by the Python community. The name Python, by the way, derives not from the snake, but from the British comedy troupe Monty Python’s Flying Circus, of which Guido was, and presumably still is, a fan. It is common to find references to Monty Python sketches and movies scattered throughout the Python documentation.

Why Choose Python?¶

If you’re going to write programs, there are literally dozens of commonly used languages to choose from. Why choose Python? Here are some of the features that make Python an appealing choice.

Python is Popular¶

Python has been growing in popularity over the last few years. The 2018 Stack Overflow Developer Survey ranked Python as the 7th most popular and the number one most wanted technology of the year. World-class software development companies around the globe use Python every single day.

According to research by Dice Python is also one of the hottest skills to have and the most popular programming language in the world based on the Popularity of Programming Language Index.

Due to the popularity and widespread use of Python as a programming language, Python developers are sought after and paid well. If you’d like to dig deeper into Python salary statistics and job opportunities, you can do so here.

Python is Interpreted¶

Many languages are compiled, meaning the source code you create needs to be translated into machine code, the language of your computer’s processor, before it can be run. Programs written in an interpreted language are passed straight to an interpreter that runs them directly.

This makes for a quicker development cycle because you just type in your code and run it, without the intermediate compilation step.

One potential downside to interpreted languages is execution speed. Programs that are compiled into the native language of the computer processor tend to run more quickly than interpreted programs. For some applications that are particularly computationally intensive, like graphics processing or intense number crunching, this can be limiting.

In practice, however, for most programs, the difference in execution speed is measured in milliseconds, or seconds at most, and not appreciably noticeable to a human user. The expediency of coding in an interpreted language is typically worth it for most applications.

Python is Free¶

The Python interpreter is developed under an OSI-approved open-source license, making it free to install, use, and distribute, even for commercial purposes.

A version of the interpreter is available for virtually any platform there is, including all flavors of Unix, Windows, macOS, smartphones and tablets, and probably anything else you ever heard of. A version even exists for the half dozen people remaining who use OS/2.

Python is Portable Because Python code is interpreted and not compiled into native machine instructions, code written for one platform will work on any other platform that has the Python interpreter installed. (This is true of any interpreted language, not just Python.)

Python is Simple¶

As programming languages go, Python is relatively uncluttered, and the developers have deliberately kept it that way.

A rough estimate of the complexity of a language can be gleaned from the number of keywords or reserved words in the language. These are words that are reserved for special meaning by the compiler or interpreter because they designate specific built-in functionality of the language.

Python 3 has 33 keywords, and Python 2 has 31. By contrast, C++ has 62, Java has 53, and Visual Basic has more than 120, though these latter examples probably vary somewhat by implementation or dialect.

Python code has a simple and clean structure that is easy to learn and easy to read. In fact, as you will see, the language definition enforces code structure that is easy to read.

But It’s Not That Simple¶

For all its syntactical simplicity, Python supports most constructs that would be expected in a very high-level language, including complex dynamic data types, structured and functional programming, and object-oriented programming.

Additionally, a very extensive library of classes and functions is available that provides capability well beyond what is built into the language, such as database manipulation or GUI programming.

Python accomplishes what many programming languages don’t: the language itself is simply designed, but it is very versatile in terms of what you can accomplish with it.

Integers¶

In Python 3, there is effectively no limit to how long an integer value can be. Of course, it is constrained by the amount of memory your system has, as are all things, but beyond that an integer can be as long as you need it to be:

print(123123123123123123123123123123123123123123123123 + 1)

# Python interprets a sequence of decimal digits without any prefix to be a decimal number:

print(10)

print(type(10))

Floating-Point Numbers¶

The float type in Python designates a floating-point number. float values are specified with a decimal point. Optionally, the character e or E followed by a positive or negative integer may be appended to specify scientific notation:

print(4.2)

print(type(4.2))

print(4.)

print(.2)

print(.4e7)

print(4.2e-4)

Strings¶

Strings are sequences of character data. The string type in Python is called str.

String literals may be delimited using either single or double quotes. All the characters between the opening delimiter and matching closing delimiter are part of the string:

print("Hacktiv8 x Inalum")

print(type("Hacktiv8 x Inalum"))

A string in Python can contain as many characters as you wish. The only limit is your machine’s memory resources. A string can also be empty:

print('')

print("This string contains a single quote (') character.")

print('This string contains a double quote (") character.')

Boolean Type, Boolean Context, and “Truthiness”¶

Python 3 provides a Boolean data type. Objects of Boolean type may have one of two values, True or False:

print(type(True))

print(type(False))

Variable Assignment¶

Think of a variable as a name attached to a particular object. In Python, variables need not be declared or defined in advance, as is the case in many other programming languages. To create a variable, you just assign it a value and then start using it. Assignment is done with a single equals sign (=):

n = 300

print(n)

n

# Later, if you change the value of n and use it again, the new value will be substituted instead:

n = 1000

print(n)

n

Python also allows chained assignment, which makes it possible to assign the same value to several variables simultaneously:

a = b = c = 300

print(a, b, c)

Variable Types in Python¶

In many programming languages, variables are statically typed. That means a variable is initially declared to have a specific data type, and any value assigned to it during its lifetime must always have that type.

Variables in Python are not subject to this restriction. In Python, a variable may be assigned a value of one type and then later re-assigned a value of a different type:

var = 23.5

print(var)

var = "Now I'm a string"

print(var)

Variable Names¶

The examples you have seen so far have used short, terse variable names like m and n. But variable names can be more verbose. In fact, it is usually beneficial if they are because it makes the purpose of the variable more evident at first glance.

Officially, variable names in Python can be any length and can consist of uppercase and lowercase letters (A-Z, a-z), digits (0-9), and the underscore character (_). An additional restriction is that, although a variable name can contain digits, the first character of a variable name cannot be a digit.

name = "Hacktiv8"

Age = 54

has_laptops = True

print(name, Age, has_laptops)

But this one is not, because a variable name can’t begin with a digit:

9_kepala_naga = True

Note that case is significant. Lowercase and uppercase letters are not the same. Use of the underscore character is significant as well. Each of the following defines a different variable:

age = 1

Age = 2

aGe = 3

AGE = 4

a_g_e = 5

_age = 6

age_ = 7

_AGE_ = 8

print(age, Age, aGe, AGE, a_g_e, _age, age_, _AGE_)

On the other hand, they aren’t all necessarily equally legible. As with many things, it is a matter of personal preference, but most people would find the first two examples, where the letters are all shoved together, to be harder to read, particularly the one in all capital letters. The most commonly used methods of constructing a multi-word variable name are the last three examples:

Camel Case: Second and subsequent words are capitalized, to make word boundaries easier to see. (Presumably, it struck someone at some point that the capital letters strewn throughout the variable name vaguely resemble camel humps.)

Example: numberOfCollegeGraduatesPascal Case: Identical to Camel Case, except the first word is also capitalized.

Example: NumberOfCollegeGraduatesSnake Case: Words are separated by underscores.

Example: number_of_college_graduates

Programmers debate hotly, with surprising fervor, which of these is preferable. Decent arguments can be made for all of them. Use whichever of the three is most visually appealing to you. Pick one and use it consistently.

Operators and Expressions in Python¶

In Python, operators are special symbols that designate that some sort of computation should be performed. The values that an operator acts on are called operands.

Here is an example:

a = 10

b = 20

a + b

In this case, the + operator adds the operands a and b together. An operand can be either a literal value or a variable that references an object:

a = 10

b = 20

a + b - 5

A sequence of operands and operators, like a + b - 5, is called an expression. Python supports many operators for combining data objects into expressions.

Aritmetic Operators¶

# Here are some examples of these operators in use:

a = 4

b = 3

print(a + b)

print(a - b)

print(a * b)

print(a / b)

print(a % b)

print(a ** b)

# The result of standard division (/) is always a float, even if the dividend is evenly divisible by the divisor:

10 / 5

Comparison Operators¶

# Here are examples of the comparison operators in use:

a = 10

b = 20

print(a == b)

print(a != b)

print(a <= b)

print(a >= b)

a = 30

b = 30

print(a == b)

print(a <= b)

print(a >= b)

String Manipulation¶

# + Operators

s = 'foo'

t = 'bar'

u = 'baz'

print(s + t)

print(s + t + u)

print('Hacktiv8 ' + 'Inalum')

# * Operators

s = 'foo.'

s * 4

# in Operators

s = 'foo'

print(s in 'That food for us')

print(s in 'That good for us')

# Case Conversion

s = 'HackTIV8 iNAlum'

# Capitalize

print(s.capitalize())

# Lower

print(s.lower())

# Swapcase

print(s.swapcase())

# Title

print(s.title())

# Uppercase

print(s.upper())

Python Lists¶

In short, a list is a collection of arbitrary objects, somewhat akin to an array in many other programming languages but more flexible. Lists are defined in Python by enclosing a comma-separated sequence of objects in square brackets ([]), as shown below:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux']

print(a)

The important characteristics of Python lists are as follows:

- Lists are ordered.

- Lists can contain any arbitrary objects.

- List elements can be accessed by index.

- Lists can be nested to arbitrary depth.

- Lists are mutable.

- Lists are dynamic.

Lists Are Ordered¶

A list is not merely a collection of objects. It is an ordered collection of objects. The order in which you specify the elements when you define a list is an innate characteristic of that list and is maintained for that list’s lifetime. (You will see a Python data type that is not ordered in the next tutorial on dictionaries.)

Lists that have the same elements in a different order are not the same:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux']

b = ['baz', 'qux', 'bar', 'foo']

a == b

Lists Can Contain Arbitrary Objects¶

A list can contain any assortment of objects. The elements of a list can all be the same type:

a = [21.42, 'foobar', 3, 4, 'bark', False, 3.14159]

print(a)

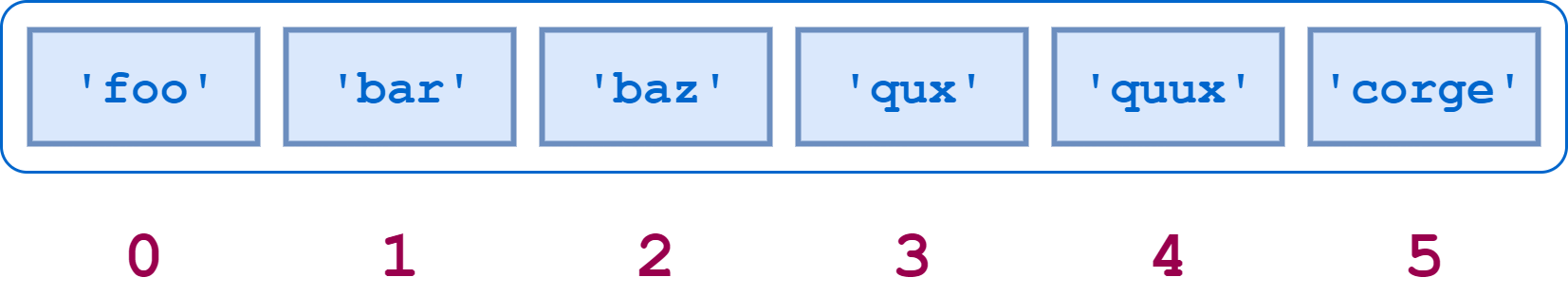

List Elements Can Be Accessed by Index¶

Individual elements in a list can be accessed using an index in square brackets. This is exactly analogous to accessing individual characters in a string. List indexing is zero-based as it is with strings.

Consider the following list:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux', 'corge']

print(a[0])

print(a[5])

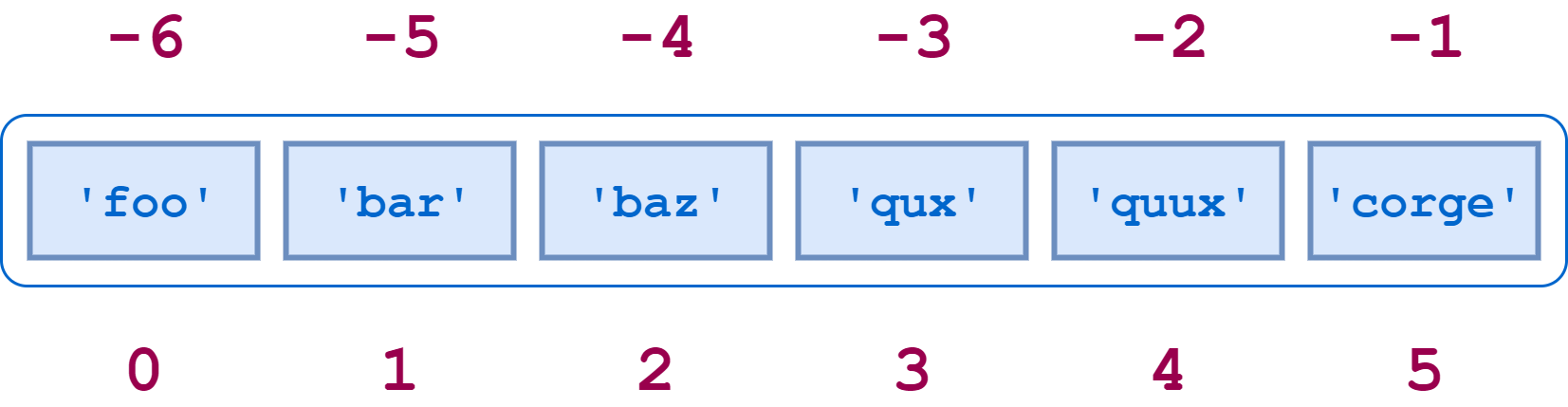

Virtually everything about string indexing works similarly for lists. For example, a negative list index counts from the end of the list:

print(a[-1])

print(a[-6])

Slicing also works. If a is a list, the expression a[m:n] returns the portion of a from index m to, but not including, index n:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux', 'corge']

a[2:5]

# The concatenation (+) and replication (*) operators:

print(a)

print(a + ['grault', 'garply'])

print(a * 2)

# len(), min(), max()

print(a)

print(len(a))

print(min(a))

print(max(a))

Modifying a Single List Value¶

A single value in a list can be replaced by indexing and simple assignment:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux', 'corge']

print(a)

a[2] = 10

a[-1] = 20

print(a)

# A list item can be deleted with the del command:

del a[3]

print(a)

Modifying Multiple List Values¶

What if you want to change several contiguous elements in a list at one time? Python allows this with slice assignment, which has the following syntax:

a = ['foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux', 'corge']

print(a[1:4])

a[1:4] = [1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, 5.5]

print(a)

Python Tuples¶

Python provides another type that is an ordered collection of objects, called a tuple.

Pronunciation varies depending on whom you ask. Some pronounce it as though it were spelled “too-ple” (rhyming with “Mott the Hoople”), and others as though it were spelled “tup-ple” (rhyming with “supple”). My inclination is the latter, since it presumably derives from the same origin as “quintuple,” “sextuple,” “octuple,” and so on, and everyone I know pronounces these latter as though they rhymed with “supple.”

Defining and Using Tuples¶

Tuples are identical to lists in all respects, except for the following properties:

Tuples are defined by enclosing the elements in parentheses (()) instead of square brackets ([]). Tuples are immutable. Here is a short example showing a tuple definition, indexing, and slicing:

t = ('foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux', 'quux', 'corge')

print(t)

print(t[0])

print(t[-1])

# packing and unpacking

(s1, s2, s3, s4) = ('foo', 'bar', 'baz', 'qux')

s1

Python Dictionary¶

ictionaries and lists share the following characteristics:

- Both are mutable.

- Both are dynamic. They can grow and shrink as needed.

- Both can be nested. A list can contain another list. A dictionary can contain another dictionary. A dictionary can also contain a list, and vice versa.

Dictionaries differ from lists primarily in how elements are accessed:

- List elements are accessed by their position in the list, via indexing.

- Dictionary elements are accessed via keys.

Defining a Dictionary¶

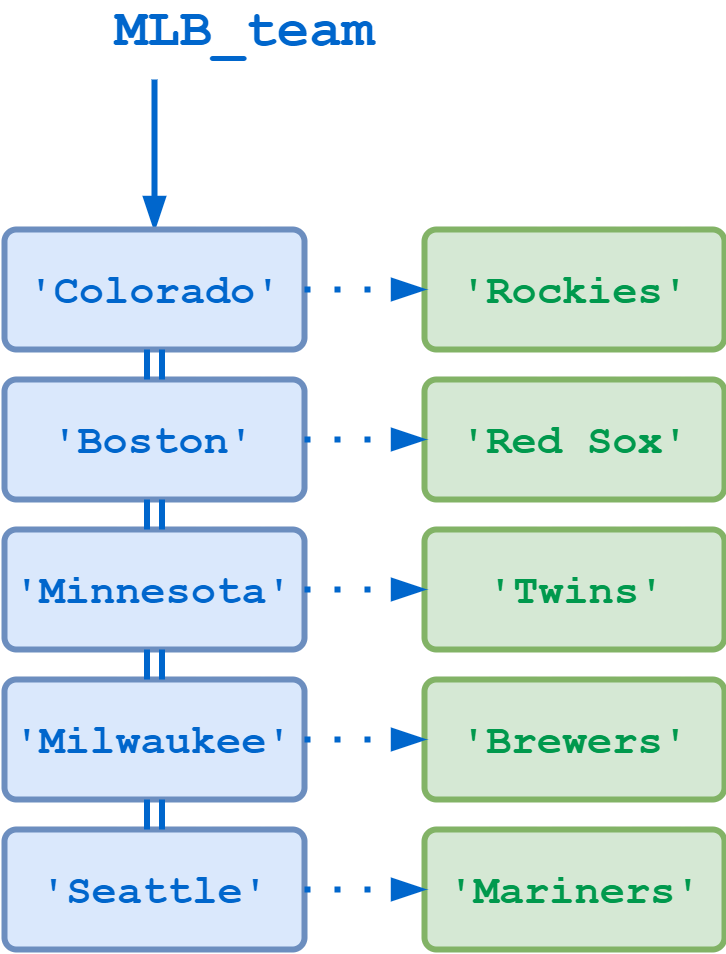

Dictionaries are Python’s implementation of a data structure that is more generally known as an associative array. A dictionary consists of a collection of key-value pairs. Each key-value pair maps the key to its associated value.

You can define a dictionary by enclosing a comma-separated list of key-value pairs in curly braces ({}). A colon (:) separates each key from its associated value.

The following defines a dictionary that maps a location to the name of its corresponding Major League Baseball team:

MLB_team = {

'Colorado': 'Rockies',

'Boston': 'Red Sox',

'Minnesota': 'Twins',

'Milwaukee': 'Brewers',

'Seattle': 'Mariners'

}

Accessing Dictionary Values¶

Of course, dictionary elements must be accessible somehow. If you don’t get them by index, then how do you get them?

A value is retrieved from a dictionary by specifying its corresponding key in square brackets ([]):

print(MLB_team['Minnesota'])

print(MLB_team['Colorado'])

# error

# MLB_team['Toronto']

#Adding an entry to an existing dictionary is simply a matter of assigning a new key and value:

MLB_team['Kansas City'] = 'Royals'

MLB_team

# If you want to update an entry, you can just assign a new value to an existing key:

MLB_team['Seattle'] = 'Seahawks'

MLB_team

# To delete an entry, use the del statement, specifying the key to delete:

del MLB_team['Seattle']

MLB_team

Building a Dictionary Incrementally¶

Defining a dictionary using curly braces and a list of key-value pairs, as shown above, is fine if you know all the keys and values in advance. But what if you want to build a dictionary on the fly?

You can start by creating an empty dictionary, which is specified by empty curly braces. Then you can add new keys and values one at a time:

person = {}

type(person)

person['fname'] = 'Hack'

person['lname'] = 'Inalum'

person['age'] = 51

person['spouse'] = 'Edna'

person['children'] = ['Ralph', 'Betty', 'Joey']

person['pets'] = {'dog': 'Fido', 'cat': 'Sox'}

person

print(person['fname'])

print(person['lname'])

print(person['children'])

print(person['children'][1])

print(person['pets'])

print(person['pets']['cat'])

# Built-in Methods

d = {'a': 10, 'b': 20, 'c': 30}

# items

print(d.items())

# keys

print(d.keys())

# values

print(d.values())

You have now covered Python variables, operators, and data types in depth, and you’ve seen quite a bit of example code. Up to now, the code has consisted of short individual statements, simply assigning objects to variables or displaying values.

But you want to do more than just define data and display it! Let’s start arranging code into more complex groupings.

Python Statements¶

Statements are the basic units of instruction that the Python interpreter parses and processes. In general, the interpreter executes statements sequentially, one after the next as it encounters them. (You will see in the next tutorial on conditional statements that it is possible to alter this behavior.)

In a REPL session, statements are executed as they are typed in, until the interpreter is terminated. When you execute a script file, the interpreter reads statements from the file and executes them until end-of-file is encountered.

Python programs are typically organized with one statement per line. In other words, each statement occupies a single line, with the end of the statement delimited by the newline character that marks the end of the line. The majority of the examples so far in this tutorial series have followed this pattern:

print('Hello, World!')

x = [1, 2, 3]

print(x)

Line Continuation¶

Suppose a single statement in your Python code is especially long. For example, you may have an assignment statement with many terms:

person1_age = 42

person2_age = 16

person3_age = 71

someone_is_of_working_age = (person1_age >= 18 and person1_age <= 65) or (person2_age >= 18 and person2_age <= 65) or (person3_age >= 18 and person3_age <= 65)

someone_is_of_working_age

someone_is_of_working_age = (

(person1_age >= 18 and person1_age <= 65)

or (person2_age >= 18 and person2_age <= 65)

or (person3_age >= 18 and person3_age <= 65)

)

someone_is_of_working_age